Feldenkraisģ &

Anat Baniel

Methodsm

for children and adults

in Bellevue, WA

425-641-4779

Blog

"In short, health is measured by the shock a person

can take without

his usual way of life being compromised." Moshe

Feldenkrais, D.Sc.

|

February 2018: Walking on my own two feet

If youíve never had a broken bone, this post may be more detail than youíre interested in. But if youíve gone through a similar recovery process, you may find it somehow satisfying to read about another personís journey. I know I did, spending a few late nights pouring over blog posts, wondering what I could do to speed my healing journey. At first when I came out of the boot, my toe was stuck pointing upwards, still swollen, and not able to touch the ground. Tapping my toe felt like moving a block of wood, and my whole foot felt more like a club than something that has 26 bones, 33 joints and more than 100 muscles, tendons, and ligaments. With all that complexity, itís not surprising that my brain had a lot to relearn. But Iím impatient, and somehow thought I could be fully functional right away. Wrong! I almost cried with joy on day 1, carrying my groceries down the stairs to my house. Having two hands free is the best part of being off crutches, and not having to plan so far in advance to make sure I always have what I need. Most of that first day was spent just in pleasure at being able to get back to life. Some of my first explorations were using my hand to gently explore each joint in my foot, waking up the connections and range of motion in each joint. Classic PT exercises Ė scrunching up a towel, picking up marbles with my toes, and raising up on my toes were well beyond me. One measurement of toe coordination and strength is to put the ends of the toes on a scale and push down Ė 3 pounds with my left was all I could do. I started working with flexion, curling up my body, my fists, and my feet all at the same time, thinking of making domes in my hands and feet. I played with rocking around my feet, circling my body above my feet to put pressure in different areas, and pushing through the wall in as many positions as I could think of. On day 2 I made it up a set of stairs, alternating one foot then the other. Down took another week: putting the toes down and rolling through my foot felt like foreign territory. During the first few days, many times a day, I tried doing exercises like lifting up the middle of my foot and sliding my toes toward my heels, writing the alphabet with my big toe, and playing imaginary piano with my toes. The foot and hand are mapped quite closely in the motor cortex, so I did the same movements with both at the same time to help the foot learn. And I took the demand down on the classic exercises, lying on my back with my feet standing, and beginning to lift my heel. Strange to feel my calf quivering with such a small exertion. On day 3, with my big toe newly touching the ground, I walked ĺ of a mile Ė too much, and I developed pain under my 3rd and 4th metatarsal/toe joints. I tried bicycling a stationary bicycle Ė that felt great, and when I discovered my gym had a live feed for the Olympic, bicycling became the go to exercise. On day 5 I tried waltzing. And like with most things, I jump in a little fast. So not 10 minutes of waltzing, but a 3 hour class. I made it most of the way through, but could not do a left-turning waltz. Pushing off and twisting did not feel good. So many things I did automatically that I now have to relearn. Then life got busier, and I stopped keeping notes. Kind of like with baby pictures: lots of detailed attention at the beginning, then time speeds on by. But I've been keeping up my daily Feldenkrais lessons and explorations with my foot. On Sunday, day 16, I was able to do a 2 mile hike without pain and a few hours of garden cleanup, including carrying trash cans up two flights of stairs. Flexion throughout the foot is getting better, but still has room to improve. I haven't tried skating yet. And definitely no running for at least another month. Iíd love to hear your stories of how long it took to feel normal after a broken bone healed Ė and what worked and didnít in your recovery. Email me at Irene@movebeyondlimits.com. 2017: A year of recovery |

|||

|

|

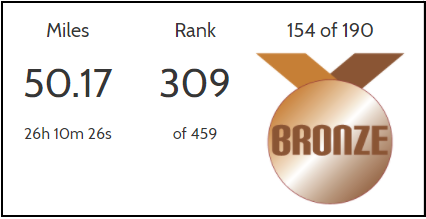

What a year! After a winter filled with delight in trail running, building up to a glorious rainy-day trail race and running with participants from my Feldenkrais for runners class, I made the classic running mistake of increasing mileage too fast. Persistent foot pain inspired a deep-dive into understanding running form and foot anatomy, followed by a trip to the doctor for an x-ray, and diagnosis of a stress fracture in my heel bone. After spending the summer in a walking boot, I restarted dancing and skating, hobbies I'd neglected during my year of falling in love with running. Over Thanksgiving weekend, I began exploring transferring my inline skills to ice and set my sights on trying synchronized skating. Life felt like it was beginning to get back to "normal" and I was delighting in feeling my skills improve. |

|

|

Then, while getting dressed and contemplating what to wear for ice skating, a vase jumped off my dresser, shattered my big toe, and changed those plans! These have been my first broken bones, and I've never had to cope with an immobilized body part before. With foot 1 in a boot, I could still walk. I thought that was bad. With foot 2, I can't bear weight until mid-January at the earliest. And crutches take away the hands, as well as the feet, setting up some new challenges. When we use the Feldenkrais Method to help people, the core principles that guide our work apply to emotions, as well as to physical challenges. With two similar injuries this year, I'm being more conscious of using these principles this time, which is helping keep anxiety and depression at bay. I'll let you know once the boot is off, but I'm expecting it to be a faster recovery from immobilization. Here are some of the principles: |

The vase that changed my plans |

-

Flexible goals: "Embrace all the unexpected steps, mis-steps, and re-routes. They are a rich source of valuable information for your brain to lead you to your goal." Anat Baniel, founder Anat Baniel Method

If my goal is synchronized skating, and I can't stand or skate or dance, I need to find different ways to keep moving and building my self-organization and balance. I'm using this in two ways:-

Immersing myself in new Feldenkrais lessons each day gives me a chance to imagine using my foot and toes, improve my breathing, balance and coordination, and most importantly reset my mood into calmness as my body lets go of unnecessary tension. This has also led me to put together some new workshops that I'm excited to share with you.

-

Finding ways to dance that I can do: Nia which encourages me to dance however I can: on the floor, in a chair, or on my scooter, and great dance workshops where I sit on the side, imagine dancing, and study how excellent teachers teach, and students learn.

-

-

"If you know what you're doing, you can do what you want." Moshe Feldenkrais, DSc.

I've thought about writing a blog for years, but this is the first time I've actually written a post. Writing it down makes me observe myself. There's a clear pattern to how I react to injury: denial, rage, depression, followed by "Ok, this is real, what can I do to stay sane, and what's the learning." Seeing this pattern opens the possibility that other responses are possible in any given moment. I have a choice in how I respond. -

"How do you find support from the ground?" Jeff Haller, PhD, Feldenkrais Trainer

On the physical side, learning how to find support from crutches, and improving my one-foot balance has helped me master getting around without touching one foot down. (Try getting up from the floor or even the toilet without letting any part of one foot touch the ground - not so easy!) On the emotional side, one of the first things I did was to hire someone to help me get done the things I can't do without use of my hands, and to say yes to offers of support from friends and family. -

Constrict one part of the body to encourage other parts to participate in the movement.

Even though it is an involuntary constriction, thinking about this principle shifts me from frustration to curiosity, a much happier place to be. And the constrictions on activities have given more time to other parts of life, like visiting with friends and family, returning to activities I can still do, and giving me more time for studying. -

"Use variation to discover new possibilities." Anat Baniel, founder Anat Baniel Method

I'm using a variety of assistive devices to get around, each of which is useful and uncomfortable in its own way. By alternating, I've expanded what I can do: crutches are great for stairs and curbs, the knee scooter is handy around the house and for errands, and the peg-leg crutch is good for dancing and pushing a grocery cart. The variation helps avoid the sore wrists and shoulders from crutches, knee pain from the knee scooter, and the occasional moments of terror when using the peg-leg crutch.

My husband used to end his email signature with the words "Accidental techie". This year I'm the "accidental recoverer". I think we're all always recovering from some shock to our nervous system or body, and I'm grateful that my profession provides such useful tools.

"What Iím after isnít flexible bodies, but flexible

brains.

What Iím after is to restore each person to their human dignity."

Moshe Feldenkrais, DSc.